Friday, September 21, 2012

I'm not back.

If you've been watching this space anxiously, I'm sorry to disappoint. I'll be back sometime, but for now the demands of my PhD are taking precedence. I do have one thing to post here, though. It doesn't fit the theme of the blog, but I think this is the best place for it. Watch this space for an open letter to the people in charge at DC and Marvel.

Wednesday, April 25, 2012

Women and (super)Men

Let's try to take a look at Action Comics #1 (the 1938 one, not the New 52 one) from a feminist perspective, and see what we come up with.

The first thing to note, of course, is that Superman is gendered. That might seem like a stupid thing to point out; of course Superman is gendered. Isn't everyone? There's no such thing as a gender-neutral person, is there? But there are two important things to notice here. Firstly, the division of all of humanity into one of two gender categories is not necessarily as obvious as it may seem--we'll leave that point to the side for now--but secondly, there's no reason that the "man" part of Superman has to be there. Superman has had such an influence on superhero nomenclature (Batman, Spider-man, Aquaman, Hawkman, Plastic Man, Iron Man, Ant-Man, Giant-Man, X-Men, not to mention Wonder Woman, Batgirl, Hawkgirl, Power Girl, etc) that we can easily forget that there's no inherent reason why a superhero's name needs to be gendered. But Superman is not just a super person, he's a super MAN, and it is implicit in his identity from the beginning that whatever else he is he is a figure of idealized hyper-masculinity.

Superman's first real appearance in the comic (real appearance as opposed to a brief expositional flashback) shows him carrying a woman who has been bound and gagged. The gender politics of that first image should be clear, the (super)man is in motion and has full agency, while the woman is completely powerless. We later learn that this bound woman is a "murderess," and Superman's hurry here is to convince the governor to pardon an innocent woman who is about to be executed in favour of having this blonde woman arrested.

A few pages later Superman has a second--indirect--interaction with a woman. Clark Kent, in his role as a reporter, has been called to report on "a phoned tip" of "a wife-beating." He arrives as Superman:

The paradigm set up here is of woman as either criminal or victim. Although it is true that Superhero comics tend to be populated with many criminals and victims in general, by this point in the comic we have seen sixteen male figures of whom one is a criminal and four female figures of whom two were victims and one was a criminal. Women here mostly conform to the "damsels in distress" trope, and they exist fundamentally so that the figure of hypermasculinity will have someone appropriately weak to rescue.

Lois Lane is both a famous example of this tendency in Superman comics and also a subversion of it. On one hand here and for much of her presence in Superman stories in all media Lois is Superman's built-in damsel-in-distress.

On the other hand Lois' character is, even in this first outing, a more developed character than are the other damsels/victims, and her relationship to Clark/Superman is not limited to being rescued. Lois is one of the vertices of a love triangle between Lois, Clark, and Superman. Clark loves Lois, but she spurns him. Lois loves Superman. In this first comic the love triangle is barely developed--certainly Lois' affection for Superman is not yet established. But here is what we do see:

Lois is established here as symbolic of an unattainable woman. Clark pursues her--and the "for once" line lets us know that he makes a habit of it--but he is usually ineffective. She's cold and aloof yet desirable, and while we might say that this is partly because she is not a human character but an object Clark wishes to possess, we might also note that she is given real agency and a real personality here.

Lois avoids Clark because he's a coward, and we see here that Lois' strength is one of the things Clark admires about her. The preoccupation with strength is a theme in Superman comics, especially as created by Siegel and Shuster. The emphasis on strength is part of an emphasis on masculinity, and Siegel and Shuster define manliness as strength.

And there you have it: a preliminary examination of some of the gender politics in Action Comics #1; a feminist reading of Superman.

The first thing to note, of course, is that Superman is gendered. That might seem like a stupid thing to point out; of course Superman is gendered. Isn't everyone? There's no such thing as a gender-neutral person, is there? But there are two important things to notice here. Firstly, the division of all of humanity into one of two gender categories is not necessarily as obvious as it may seem--we'll leave that point to the side for now--but secondly, there's no reason that the "man" part of Superman has to be there. Superman has had such an influence on superhero nomenclature (Batman, Spider-man, Aquaman, Hawkman, Plastic Man, Iron Man, Ant-Man, Giant-Man, X-Men, not to mention Wonder Woman, Batgirl, Hawkgirl, Power Girl, etc) that we can easily forget that there's no inherent reason why a superhero's name needs to be gendered. But Superman is not just a super person, he's a super MAN, and it is implicit in his identity from the beginning that whatever else he is he is a figure of idealized hyper-masculinity.

Superman's first real appearance in the comic (real appearance as opposed to a brief expositional flashback) shows him carrying a woman who has been bound and gagged. The gender politics of that first image should be clear, the (super)man is in motion and has full agency, while the woman is completely powerless. We later learn that this bound woman is a "murderess," and Superman's hurry here is to convince the governor to pardon an innocent woman who is about to be executed in favour of having this blonde woman arrested.

A few pages later Superman has a second--indirect--interaction with a woman. Clark Kent, in his role as a reporter, has been called to report on "a phoned tip" of "a wife-beating." He arrives as Superman:

The paradigm set up here is of woman as either criminal or victim. Although it is true that Superhero comics tend to be populated with many criminals and victims in general, by this point in the comic we have seen sixteen male figures of whom one is a criminal and four female figures of whom two were victims and one was a criminal. Women here mostly conform to the "damsels in distress" trope, and they exist fundamentally so that the figure of hypermasculinity will have someone appropriately weak to rescue.

Lois Lane is both a famous example of this tendency in Superman comics and also a subversion of it. On one hand here and for much of her presence in Superman stories in all media Lois is Superman's built-in damsel-in-distress.

On the other hand Lois' character is, even in this first outing, a more developed character than are the other damsels/victims, and her relationship to Clark/Superman is not limited to being rescued. Lois is one of the vertices of a love triangle between Lois, Clark, and Superman. Clark loves Lois, but she spurns him. Lois loves Superman. In this first comic the love triangle is barely developed--certainly Lois' affection for Superman is not yet established. But here is what we do see:

Lois is established here as symbolic of an unattainable woman. Clark pursues her--and the "for once" line lets us know that he makes a habit of it--but he is usually ineffective. She's cold and aloof yet desirable, and while we might say that this is partly because she is not a human character but an object Clark wishes to possess, we might also note that she is given real agency and a real personality here.

Lois avoids Clark because he's a coward, and we see here that Lois' strength is one of the things Clark admires about her. The preoccupation with strength is a theme in Superman comics, especially as created by Siegel and Shuster. The emphasis on strength is part of an emphasis on masculinity, and Siegel and Shuster define manliness as strength.

And there you have it: a preliminary examination of some of the gender politics in Action Comics #1; a feminist reading of Superman.

Labels:

comics theory,

feminism,

superman

Wednesday, April 11, 2012

Feminist Superman

Feminist theory covers a lot of ground and a lot of approaches to literature. The simplest way to understand feminist criticism is to say that a feminist reading of a text is one that focuses on women.

Sometimes that means focusing on books that were written by women--often as a way of correcting a historical inequality. For most of the history of literature most of the books that have been seriously studied have been written by men--but men were never the only people writing. Feminist criticism is a way to try to fix what we read and who wrote it. This kind of feminist reading would point out that there have proportionally been very few women who write comics for DC, but would draw our attention to women like Dorothy Woolfolk, Mindy Newell, and Gail Simone.

Sometimes that means focusing on female characters in stories--again often as a way of correcting historical inequality. Focusing on female characters in a feminist context can mean a lot of different things, but in brief it always has to mean focusing on the female characters themselves, instead of just focusing on how they relate to male characters. So talking about Lois Lane is a start but if we're talking about Superman's girlfriend Lois Lane then we're still defining her as a character in terms of her relationship to a male character. A feminist reading might instead want to talk about Lois Lane herself. Or even a focus on Superman can be feminist in this way if it is a focus on Superman as Lois Lane's boyfriend.

Sometimes that means focusing on gender in general. Certain strains of feminist theory have stressed that "woman" as a category is invented by culture, and that it is defined in contradiction to "man" as a category. So a reading of Superman that focuses on how Superman is a representative of masculinity, especially when that reading emphasizes the way masculinity is socially constructed and the way that it simultaneously constructs femininity, might also be a feminist reading.

Those are only three of many ways to do feminist criticism, but I hope you are getting a picture of how much scope there is in feminist criticism. I'll be back soon with a second post on feminist criticism, where we will actually do a (brief) feminist reading of Action Comics 1.

Sometimes that means focusing on books that were written by women--often as a way of correcting a historical inequality. For most of the history of literature most of the books that have been seriously studied have been written by men--but men were never the only people writing. Feminist criticism is a way to try to fix what we read and who wrote it. This kind of feminist reading would point out that there have proportionally been very few women who write comics for DC, but would draw our attention to women like Dorothy Woolfolk, Mindy Newell, and Gail Simone.

Sometimes that means focusing on female characters in stories--again often as a way of correcting historical inequality. Focusing on female characters in a feminist context can mean a lot of different things, but in brief it always has to mean focusing on the female characters themselves, instead of just focusing on how they relate to male characters. So talking about Lois Lane is a start but if we're talking about Superman's girlfriend Lois Lane then we're still defining her as a character in terms of her relationship to a male character. A feminist reading might instead want to talk about Lois Lane herself. Or even a focus on Superman can be feminist in this way if it is a focus on Superman as Lois Lane's boyfriend.

Sometimes that means focusing on gender in general. Certain strains of feminist theory have stressed that "woman" as a category is invented by culture, and that it is defined in contradiction to "man" as a category. So a reading of Superman that focuses on how Superman is a representative of masculinity, especially when that reading emphasizes the way masculinity is socially constructed and the way that it simultaneously constructs femininity, might also be a feminist reading.

Those are only three of many ways to do feminist criticism, but I hope you are getting a picture of how much scope there is in feminist criticism. I'll be back soon with a second post on feminist criticism, where we will actually do a (brief) feminist reading of Action Comics 1.

Labels:

comics as literature,

comics theory,

feminism

Tuesday, February 21, 2012

I Like Racist Things

Sexist, too.

All right, calm down everybody.

I don't mean that I like these things because they're racist/sexist/whatever. It's not that I go out looking for racist stuff to enjoy. A better, less provocative way of putting it would be "Things I like are Racist".

But look, I read comic books and Medieval literature. I can't pretend that stuff is unproblematic. More, I don't think it is right to pretend it's unproblematic. I think it's bad scholarship, and I think it's bad human-ship. But let's not get ahead of ourselves. What is the problem here, and what can we do about it?

I've posted a (slightly) different version of this on Medievalala too, because the issues I'm going to write about here really concern both medieval literature and comics--especially the kind of comics I usually focus on.

The Problem with Comics

Although my title references racism specifically, I'm concerned here with the whole rainbow of discrimination: racism, sexism, ablism, heteronormativism, classism, beautyism, sizeism you name it. While arguably all literature and definitely all categories of literature contain some problematic stuff, mainstream superhero comics are especially bad.

All right, calm down everybody.

I don't mean that I like these things because they're racist/sexist/whatever. It's not that I go out looking for racist stuff to enjoy. A better, less provocative way of putting it would be "Things I like are Racist".

But look, I read comic books and Medieval literature. I can't pretend that stuff is unproblematic. More, I don't think it is right to pretend it's unproblematic. I think it's bad scholarship, and I think it's bad human-ship. But let's not get ahead of ourselves. What is the problem here, and what can we do about it?

I've posted a (slightly) different version of this on Medievalala too, because the issues I'm going to write about here really concern both medieval literature and comics--especially the kind of comics I usually focus on.

The Problem with Comics

Although my title references racism specifically, I'm concerned here with the whole rainbow of discrimination: racism, sexism, ablism, heteronormativism, classism, beautyism, sizeism you name it. While arguably all literature and definitely all categories of literature contain some problematic stuff, mainstream superhero comics are especially bad.

In its simplest expression, the problem is this: superheroes are white.

That image is a splash page from the 2004 "Identity

Crisis" storyline. That story isn't important (yet) to this post, but

what this page is convenient because the idea of this scene is that it's

a funeral and all the major DC superheroes attend. Take a look and see

how many People of Colour you can pick out of that crowd.

I

count four obvious and a few ambiguous. And of those four only Cyborg

could really be called an A-list character. And while DC has made some

(tiny) attempts at improving lately (by adding Cyborg to the Justice

League, for example), this tiny progress does not do much to change the

landscape.

I

count four obvious and a few ambiguous. And of those four only Cyborg

could really be called an A-list character. And while DC has made some

(tiny) attempts at improving lately (by adding Cyborg to the Justice

League, for example), this tiny progress does not do much to change the

landscape.

The point is that this is a very white universe. The superheroes are white and they fight mostly for the interests of White America. DC's past attempts at addressing this have been well-intentioned but ... clumsy.

And even if DC undertook a massive about-face and made their universe truly inclusive, they still have decades of history that will still exists and that--frankly--is what I study. So the problem here doesn't go away even if the comics industry changes. Which doesn't mean that it shouldn't change, by the way. But since superhero books are primarily aspirational, and since there are so few POC characters, that means that historically readers of colour were implicitly told by comics that what they should aspire to be is white.

The sexism of comics has been so well documented and so extensively commented upon that I'm not even going to rehash it except to say that the mainstream comics industry systematically objectifies, sexualizes, and marginalizes female characters, even to the detriment of both story and sales. If you don't know what I'm talking about, just Google "Starfire new 52".

|

| Click to Enlarge. If I did it right. |

I

count four obvious and a few ambiguous. And of those four only Cyborg

could really be called an A-list character. And while DC has made some

(tiny) attempts at improving lately (by adding Cyborg to the Justice

League, for example), this tiny progress does not do much to change the

landscape.

I

count four obvious and a few ambiguous. And of those four only Cyborg

could really be called an A-list character. And while DC has made some

(tiny) attempts at improving lately (by adding Cyborg to the Justice

League, for example), this tiny progress does not do much to change the

landscape.The point is that this is a very white universe. The superheroes are white and they fight mostly for the interests of White America. DC's past attempts at addressing this have been well-intentioned but ... clumsy.

And even if DC undertook a massive about-face and made their universe truly inclusive, they still have decades of history that will still exists and that--frankly--is what I study. So the problem here doesn't go away even if the comics industry changes. Which doesn't mean that it shouldn't change, by the way. But since superhero books are primarily aspirational, and since there are so few POC characters, that means that historically readers of colour were implicitly told by comics that what they should aspire to be is white.

The sexism of comics has been so well documented and so extensively commented upon that I'm not even going to rehash it except to say that the mainstream comics industry systematically objectifies, sexualizes, and marginalizes female characters, even to the detriment of both story and sales. If you don't know what I'm talking about, just Google "Starfire new 52".

Why This is a Problem

Now I'm going to give you all the benefit of the doubt and assume that you don't actually want to marginalize, objectify, or dehumanize people. But that's what the problem here is about. Politics of representation is not just a matter of over-sensitive political-correctness. I believe that books matter, and if I didn't believe that then I wouldn't spend all my time reading them. The stories we tell and the stories we hear both shape and are shaped by our worldview. Bigotry in fiction is a problem firstly because it reveals the bigoted assumptions behind the creation of that fiction. So it should be no surprise that while the exact percentages change often and are disputed and disputable, but it is indisputable that there are, for example, far fewer women than men creating comics at DC or Marvel.

I'm not saying that these publishers need to hire women and minorities indiscriminately, or that the people creating comics are all racist and sexist as individuals, or even that the policies of DC and Marvel are sexist or racist. They may be, but that's not really my point. My point is simply that by far the bulk of comics that have ever been published by DC and Marvel were written by white men about white men the concerns of white men with a white male audience in mind. And that should bother us as readers--whether scholarly readers or simply fans. It should (and often does) bother women who read comics because they are so clearly and often aggressively the object rather than the subject of the narrative, so the narrative is alienating. It should (and often does) bother minorities who read comics because they are so often absent from the idealized world being depicted and are do not have the same scope for identification that their white counterparts have. And it should bother white male readers of comics, like me, firstly because we are being presented with an impoverished and limited world and that's boring, and secondly because (at the risk of repeating myself), we don't actually want to marginalize, objectify, or dehumanize people.

False Solutions

As a reader, whether a fan or a scholar, the solution to these problems can't be to ignore them. It can't be to deny them, or to pretend that the problematic representations in comics don't matter. The option to ignore harmful representations is the option of privilege, and exercising that option is being complicit in the racism and sexism behind those representations.

And it can't be to excuse these problematic representations on the grounds of special-circumstances: that the A-list characters are all legacies of a different time. There are many problems with this excuse, but the simplest is that no matter when things were produced they are being read now. Even if we accept the (frankly lame) excuse that writers of the past didn't know any better, readers of today do.

Possible Solutions

One possible solution, of course, is to choose something else to read. Within the medium of comics, mainstream superhero comics are not all there is. Plenty of independent comics are light-years better than DC or Marvel in terms of the politics of representation.

When you're reading for fun, this is easy. Don't read things that you don't enjoy. If the problematic elements are such that they overwhelm the pleasure of the reading then there really is no problem.

When you're reading as a scholar, whether a student reading an assigned text or a higher-level academic reading for the edification of yourself or others, the option of just not reading problematic stuff is less viable. In the first place, pretending that problematic texts don't exist is itself deeply problematic because it is an idealized and false representation of the world. In the second place, sometimes texts are just plain worth reading from an academic standpoint--whether because of their historical significance or because of artistic value or as a counterpoint to another text.

A possible solution here is to read with (faux) objectivity. A scholarly study of art or literature as an object need not imply any kind of tacit approval. There are plenty of historians who study Nazi Germany and that emphatically does not make those historians Nazis. It is possible to study the racism and/or sexism of comics directly.

But eagle-eyed readers will notice the bracketed (faux) I placed before the word "objectivity" in that last paragraph. I like Superman comics. If I read them from a position of objectivity, that is a false position and I am being disingenuous. I suspect that most academic readers of comics share this position with me. I suspect that most scholars like what they read, at least on some level. And if they don't, I think that is ... well ... sad. And they should think about changing specializations. Even historians who study atrocities often look for good in the responses to those atrocities, and it is usually not so much so that they redeem the historical period as so that they redeem the process of studying the historical period.

But academic readings do need a certain degree of, or a certain kind of objectivity. A critical analysis is not a review, and within an academic context nobody cares very much whether I like Superman better than Batman. But they might care what I think is happening within a given Superman comic, or how the character evolves or resists evolution over time. There are multitudes of angles from which to approach comics that have little to do with race or gender, and they're valid. So without arguing that the problems of representation don't matter, I can legitimately argue that they're not my point.

Which brings me back to readings for pleasure. If the problematic elements aren't enough to keep you from enjoying a text--if you do enjoy reading problematic stuff--then I think what you need to do is acknowledge the problems, and articulate the positive. This post over on the Social Justice League blog has a few good suggestions for how to approach fandom of problematic material. The author suggests that fans must acknowledge the problematic elements without attempting to defend, excuse, or gloss-over those problems. What I think is missing in her article, though, perhaps because she thought it went without saying, is that narratives are complex and the best ones are the most complex. Which, if we rephrase it in subjective terms, means that the comics you think are the best are the ones you find complexity in. Like a racist family member, you confront the text about its flaws but continue to love it despite them, maybe because of its virtues, and maybe just because of its familiarity. When I say "articulate the positive" I don't mean argue that the positive outweighs the negative, so that you can argue someone else into liking what you like. But I do mean learn to articulate what it is you like and why, even if the only one you're articulating that to is yourself.

Thoughts?

Labels:

comics theory,

ramblings

Tuesday, February 7, 2012

The Myth of Superman (no, not THAT "Myth of Superman")

The title of this post is a reference to an essay by Umberto Eco entitled "The Myth of Superman". I write about Eco's essay here.

Like a psychoanalytic reading, a mythological or archetypal reading of a text is content-based. And like psychoanalytic readings, mythological/archetypal readings are typically preoccupied with symbolism. Rather than being concerned with psychology--with the workings of a mind--however, mythological readings are concerned with mass-psychology--with the collective imaginings of all people. And though mythological/archetypal readings have in the past made a claim to account for all people, many critics now argue that archetypes are culturally bound, so when archetypal critics talk about "all people" they often really mean "all people who share our culture". On the other hand, given the effects of globalization and the ease with which cultural/mythological/archetypal ideas spread, there's a good case to be made that all cultures have interacted with all others to at least some degree.

In any case. Mythological/archetypal readings are also reminiscent of some kinds of structuralist criticism, because both often appeal to archetypal narrative elements like "the hero". In these terms, Superman seems particularly easy to read. Superman is the hero. He is an archetypal representative of masculine strength.

Clark Kent is both an archetypal representative of the hero's weakness and also of the Jungian "persona", emphasizing that the face we show to the world is not the same as our "self".

This, by the way, is the answer to the commenter on the Marxist post who pointed out that Superman's boss is only a cover, that Clark is not really allied with the proletariat because his "boss" has no real authority over him. That's definitely true.

On the other hand, part of the point of Superman is that the self is divided. Debates about whether Clark or Superman (or Bruce or Batman) is the "real" identity miss the mythological resonance that makes the secret identity such a compelling narrative archetype.

Like a psychoanalytic reading, a mythological or archetypal reading of a text is content-based. And like psychoanalytic readings, mythological/archetypal readings are typically preoccupied with symbolism. Rather than being concerned with psychology--with the workings of a mind--however, mythological readings are concerned with mass-psychology--with the collective imaginings of all people. And though mythological/archetypal readings have in the past made a claim to account for all people, many critics now argue that archetypes are culturally bound, so when archetypal critics talk about "all people" they often really mean "all people who share our culture". On the other hand, given the effects of globalization and the ease with which cultural/mythological/archetypal ideas spread, there's a good case to be made that all cultures have interacted with all others to at least some degree.

In any case. Mythological/archetypal readings are also reminiscent of some kinds of structuralist criticism, because both often appeal to archetypal narrative elements like "the hero". In these terms, Superman seems particularly easy to read. Superman is the hero. He is an archetypal representative of masculine strength.

Clark Kent is both an archetypal representative of the hero's weakness and also of the Jungian "persona", emphasizing that the face we show to the world is not the same as our "self".

|

| Definitely two different selves. |

This, by the way, is the answer to the commenter on the Marxist post who pointed out that Superman's boss is only a cover, that Clark is not really allied with the proletariat because his "boss" has no real authority over him. That's definitely true.

On the other hand, part of the point of Superman is that the self is divided. Debates about whether Clark or Superman (or Bruce or Batman) is the "real" identity miss the mythological resonance that makes the secret identity such a compelling narrative archetype.

Thursday, February 2, 2012

Superegoman

Like Marxist readings, psychoanalytic, or Freudian, readings are focused on interpreting and understanding the content of a story. There are a number of different approaches to a psychoanalytic reading of a text, and I'm just going to begin one, but I'll also suggest a possible approach to some others.

We should begin by noting that in psychoanalytic readings we differentiate between the manifest content and the latent content. In Freud's own terms, the mind is like an iceberg. What we see is the manifest 10% -- the tip of the iceberg. Everything that lies beneath the surface -- the 90% -- is latent. So a psychoanalytic reading of literature takes for granted that the apparent meaning of a text is only the tip of the iceberg, and that literature contains much more content beneath the surface.

This approach, by the way, is one that frustrates students, because it implies that there is a "secret meaning" hidden in the text. We shouldn't let that impression persist. Even within psychoanalytic readings, the latent meaning is not a "coded" or "secret" meaning that the author and the critic both understand but have hidden from the reader. Rather, it is subtext that comes from how the mind is understood to function. The author is likely no more aware of it than the reader is, and the critic is not assumed to be correctly deciphering the real meaning of the text, but to be suggesting one possible interpretation.

The three clear ways to approach a psychoanalytic reading of a text are to 1) read to psychoanalyze the characters, 2) read to psychoanalyze the author, or 3) read to discover the latent meaning of the text and describe it in the language of psychoanalysis.

In the case of Superman there are, as I said, a few good approaches. Freud suggested that the mind was divided into the id, which operates on the pleasure principle, is basically pure desire, and seeks to achieve pleasure and avoid pain; the ego which is operates on the reality principle, is basically pure reason, and seeks to rationalize action; and the superego, which is basically the seat of morals, and seeks to make the person socially acceptable and therefore "good". According to this model we can see that Superman is virtually always a manifestation of the superego, acting as a moral authority to impose good. Superman's villains, who are usually criminals against property, are manifestations of the id's desire. The Superman-superego stops the criminal-ids from acting on their desire because acting on that desire would be detrimental to society.

I'll put my cards on the table here and say that I usually don't put much stock in psychoanalytic theory myself, but plenty of people do and it's worth knowing what it is and how people approach it.

We should begin by noting that in psychoanalytic readings we differentiate between the manifest content and the latent content. In Freud's own terms, the mind is like an iceberg. What we see is the manifest 10% -- the tip of the iceberg. Everything that lies beneath the surface -- the 90% -- is latent. So a psychoanalytic reading of literature takes for granted that the apparent meaning of a text is only the tip of the iceberg, and that literature contains much more content beneath the surface.

|

| Nope. No latent psychological meaning here. |

The three clear ways to approach a psychoanalytic reading of a text are to 1) read to psychoanalyze the characters, 2) read to psychoanalyze the author, or 3) read to discover the latent meaning of the text and describe it in the language of psychoanalysis.

|

| Forcing the Governor to Act Morally |

I'll put my cards on the table here and say that I usually don't put much stock in psychoanalytic theory myself, but plenty of people do and it's worth knowing what it is and how people approach it.

Labels:

comics as literature,

comics theory,

freud

Thursday, January 26, 2012

Superman: Marxist.

Though it is true that Superman has been portrayed as a communist in at least one story, you should not understand "Marxist" as "communist". Marx was, in Foucault's terms, the founder of a discourse. He was the first to write from a certain perspective, and everyone who writes from the same perspective--even if it is to discredit Marx--is writing within the discourse of Marxism. When we're thinking about literature, any time we focus on class, or economics, we're reading from a Marxist perspective.

Though it is true that Superman has been portrayed as a communist in at least one story, you should not understand "Marxist" as "communist". Marx was, in Foucault's terms, the founder of a discourse. He was the first to write from a certain perspective, and everyone who writes from the same perspective--even if it is to discredit Marx--is writing within the discourse of Marxism. When we're thinking about literature, any time we focus on class, or economics, we're reading from a Marxist perspective.That said, there are implicit class positions in Superman comics. Grant Morrison once said in an interview that "Bruce has a butler, Clark has a boss". In his earliest incarnations, Superman continually and predictably fights against the powerful on behalf of the weak; against the rich on behalf of the poor. In one of his first appearances, in Action Comics #3, Superman rescues some trapped miners, then threatens the owner until he provides better conditions and pay for the miners. In Action Comics #8, he destroys the slums of Metropolis to force the government to rebuild them. I wrote each of these stories in a previous blog post, and I bring them up again now to stress that Superman, in his original inception, was explicitly concerned with class.

The Superman of the Silver Age (see this post for more on the "ages"), as Eco points out in his essay "The Myth of Superman", fought mostly for the protection of property. Superman, whose power in the Silver Age was such that he could (and did) easily crush coal into diamonds, and search the bottom of the sea to find sunken treasure. In other words, he was removed from the need for capital, but protected the capital of others. In contrast to Action Comics #8, the Superman of the Silver Age does nothing to change society, but instead works carefully to uphold it.

We can read any individual Superman comic through a Marxist lens, and find that the subtext changes dramatically depending on the writer and on the editor, on the political atmosphere of the time. I think that if we read Superman in general, however--if we focus on the parts of Superman that remain the same and on the impetus for the character--we'll find what in theological terms we call "a preferential option for the poor". I think Superman is fundamentally a conflicted character. He does uphold the status quo despite the fact that he has the power to change it. But Clark Kent doesn't have a butler, he has a boss.

Saturday, January 21, 2012

10 Non-Fiction Comics Worth Your Time

I've spent a lot of time on this blog so far talking about mainstream superheroes. And superheroes and the mainstream comics world is worth paying attention too--at least in my judgement. But it's far from all that's out there. In the interests of giving a wider picture, then, here are 10 non-fiction comics I think are especially worth your time. Apologies for the comics that pop up here and on other lists I've made. What can I say? I just want to recommend what I've loved reading. Also, don't place too much importance on the order these books are presented in. Another day I might order them differently.

Honourable mentions: Not actually non-fiction

Blankets - Craig Thompson

Blankets - Craig Thompson

Craig Thompson's Blankets is classified as a novel, but it is clearly at least semi-autobiographical. In this book Thompson displays great talent weaving together themes, symbols, and images. He is an excellent writer. But it is as an artist that he is simply outstanding, and this book is worth buying just so you can take your time looking at it.

Hark! A Vagrant - Kate Beaton

Kate Beaton's webcomic Hark! A Vagrant

is one of the best webcomics ever made. In this book she collects her

historical and literary comics, and adds some commentary. Some, like

the "Sexy Batman" series are clearly and straightforwardly fiction.

Others, however, represent historical figures in a parodic context that I

have to conclude counts as non-fiction. Virtually anyone will end this

well-researched book more informed than they began it.

Kate Beaton's webcomic Hark! A Vagrant

is one of the best webcomics ever made. In this book she collects her

historical and literary comics, and adds some commentary. Some, like

the "Sexy Batman" series are clearly and straightforwardly fiction.

Others, however, represent historical figures in a parodic context that I

have to conclude counts as non-fiction. Virtually anyone will end this

well-researched book more informed than they began it.

Okay here are the really-non-fiction books

10. Book of Genesis - Illustrated by R. Crumb

Robert Crumb is the founder and central figure of "underground comics". He's a satirist and a critic, a wit and an innovator. Crumb has said that he originally intended this book to be a satirical send-up of the book of Genesis, but he was swept away by the language of the Bible, and in the end he presents the text of Genesis unaltered. His illustrations are neither satirical nor psychedelic. This is simply an illustrated graphic-novel version of the book of Genesis, with all the beauty and all the humour and all the horror of the Bible maintained.

Robert Crumb is the founder and central figure of "underground comics". He's a satirist and a critic, a wit and an innovator. Crumb has said that he originally intended this book to be a satirical send-up of the book of Genesis, but he was swept away by the language of the Bible, and in the end he presents the text of Genesis unaltered. His illustrations are neither satirical nor psychedelic. This is simply an illustrated graphic-novel version of the book of Genesis, with all the beauty and all the humour and all the horror of the Bible maintained.

9.

9.  You Can Never Find a Rickshaw When It Monsoons - Mo Willems

You Can Never Find a Rickshaw When It Monsoons - Mo Willems

I've written about this book before. It's a cartoon-a-day travel journal by a young Mo Willems, written before he began a career as a writer for sesame street and then as a popular and successful children's book author. This book is a great read, and provides the reader with a glimpse of life around the globe, as it was in the early 90s.

8. The Plot - Will Eisner

The Plot - Will Eisner

Will Eisner was a major innovator in the comics world. His Contract With God is usually credited as the first graphic novel, and was certainly the first book to be marketed as such. In The Plot, Eisner recounts the history of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Part history, part polemic, The Plot is a powerful piece of anti-anti-semite writing.

7. Logicomix - Apostolos Doxiadis

Logicomix is essentially a biography of Bertrand Russell. As it tells his life story, however, it also explains Russell's life's work, and the importance of logic to Russell and to 20th century mathematics and philosophy. Well worth reading.

6. Palestine - Joe Sacco

I could probably replace this with any of Joe Sacco's books. Palestine is a fantastic piece of comics-journalism--and is the first book that could claim that title at all. In it, Sacco tours Palestine, talking to the people he meets about their day-to-day lives and about the conflict with Israel. Though Sacco generally presents these conversations without much comment, his sympathy is clearly with the Palestinians and it's difficult to read this book without sharing that sympathy.

I could probably replace this with any of Joe Sacco's books. Palestine is a fantastic piece of comics-journalism--and is the first book that could claim that title at all. In it, Sacco tours Palestine, talking to the people he meets about their day-to-day lives and about the conflict with Israel. Though Sacco generally presents these conversations without much comment, his sympathy is clearly with the Palestinians and it's difficult to read this book without sharing that sympathy.

5. American Splendor: From off the Streets Of Cleveland - Harvey Pekar

American Splendor is a series, not a single comic. There are any number of non-fiction books by Harvey Pekar that are worth your time. In addition to this book, I'd especially recommend Our Cancer Year, which is a single-narrative comic about a year relating the story of the year Pekar discovered he had testicular cancer, or American Splendor: The Life and Times of Harvey Pekar, Pekar's first anthology (which I couldn't find on amazon). Pekar's writing is often typified as "slice of life", and if you don't understand what that means, check out these two pages for a taste of American Splendor.

4. Louis Riel: A Comic-Strip Biography - Chester Brown

Chester Brown has gotten a fair bit of press lately for his memoir Paying for It, in which he recounts his experiences as a John. I haven't read that, so I can't say whether it's worth your time. Louis Riel, however, definitely is. Riel is one of the most colourful characters of Canadian history, and Brown writes an energetic and gripping account of Riel's conflicts with the Canadian government. Both his writing and his art are deceptively simple, which increases a kind of unconscious sense that he is presenting you with the simple facts. One of the simple but great things about this book is the endnotes, in which Brown comments on panels which may give a false impression of the history, and corrects that false impression; things like "McDougall arrived in Pembina by ox-cart, not stage-coach. I'm not sure why I drew stage-coaches -- there is a note in my script specifying ox-cart" (246).

3. Persepolis - Marjane Satrapi

Marjane Satrapi's memoir Persepolis and its sequel Persepolis 2 are gripping accounts of life in Iran before, during, and after Islamic Revolution. One of the things that makes this book so engaging is how unfamiliar the story is to most Westerners. This, in addition to the compelling specificity of Satrapi's life, the details of a person that we seem to really get to know, make for a great read. Unlike Maus, which is written by Art Spiegelman about his father and therefore has the benefit of hindsight, Persepolis ends with very little resolution, which is both a weakness and a strength--the lack of a narrativized ending only makes the narrative seem more real.

2. Understanding Comics - Scott McCloud

I've written about Understanding Comics before. It is one of the most popular non-fiction comics ever written, and certainly the most popular non-narrative comic ever written, and deservedly so. In Understanding Comics, McCloud dissects the medium of comics in both historical and especially in theoretical terms, and attempts to explain how comics work. He does so in an entertaining and engaging way that is well worth reading by anyone who enjoys the medium of comics.

1. Maus - Art Spiegelman

Before he wrote Maus, Art Spiegelman was known by comics fans for his experimental--sometimes radically so--art. In comparison with some of his other work, Maus is deceptively simple and straightforward. It is the story of Spiegelman's father, Vladek, a Polish Jew, during and after WWII. Spiegelman couches the story as an animal fable, drawing the Jews as mice, the Germans as cats, the Americans as dogs, etc. The only comic book ever to have won a Pulitzer Prize, this is both an outstanding comic book and an outstanding holocaust narrative.

And there you have it. This list isn't to say that there aren't plenty of other non-fiction comics which are also worth your time of course. Feel free to suggest more in the comments!

Honourable mentions: Not actually non-fiction

Blankets - Craig Thompson

Blankets - Craig ThompsonCraig Thompson's Blankets is classified as a novel, but it is clearly at least semi-autobiographical. In this book Thompson displays great talent weaving together themes, symbols, and images. He is an excellent writer. But it is as an artist that he is simply outstanding, and this book is worth buying just so you can take your time looking at it.

Hark! A Vagrant - Kate Beaton

Kate Beaton's webcomic Hark! A Vagrant

is one of the best webcomics ever made. In this book she collects her

historical and literary comics, and adds some commentary. Some, like

the "Sexy Batman" series are clearly and straightforwardly fiction.

Others, however, represent historical figures in a parodic context that I

have to conclude counts as non-fiction. Virtually anyone will end this

well-researched book more informed than they began it.

Kate Beaton's webcomic Hark! A Vagrant

is one of the best webcomics ever made. In this book she collects her

historical and literary comics, and adds some commentary. Some, like

the "Sexy Batman" series are clearly and straightforwardly fiction.

Others, however, represent historical figures in a parodic context that I

have to conclude counts as non-fiction. Virtually anyone will end this

well-researched book more informed than they began it.Okay here are the really-non-fiction books

10. Book of Genesis - Illustrated by R. Crumb

Robert Crumb is the founder and central figure of "underground comics". He's a satirist and a critic, a wit and an innovator. Crumb has said that he originally intended this book to be a satirical send-up of the book of Genesis, but he was swept away by the language of the Bible, and in the end he presents the text of Genesis unaltered. His illustrations are neither satirical nor psychedelic. This is simply an illustrated graphic-novel version of the book of Genesis, with all the beauty and all the humour and all the horror of the Bible maintained.

Robert Crumb is the founder and central figure of "underground comics". He's a satirist and a critic, a wit and an innovator. Crumb has said that he originally intended this book to be a satirical send-up of the book of Genesis, but he was swept away by the language of the Bible, and in the end he presents the text of Genesis unaltered. His illustrations are neither satirical nor psychedelic. This is simply an illustrated graphic-novel version of the book of Genesis, with all the beauty and all the humour and all the horror of the Bible maintained.  9.

9. I've written about this book before. It's a cartoon-a-day travel journal by a young Mo Willems, written before he began a career as a writer for sesame street and then as a popular and successful children's book author. This book is a great read, and provides the reader with a glimpse of life around the globe, as it was in the early 90s.

8.

Will Eisner was a major innovator in the comics world. His Contract With God is usually credited as the first graphic novel, and was certainly the first book to be marketed as such. In The Plot, Eisner recounts the history of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Part history, part polemic, The Plot is a powerful piece of anti-anti-semite writing.

7. Logicomix - Apostolos Doxiadis

Logicomix is essentially a biography of Bertrand Russell. As it tells his life story, however, it also explains Russell's life's work, and the importance of logic to Russell and to 20th century mathematics and philosophy. Well worth reading.

6. Palestine - Joe Sacco

I could probably replace this with any of Joe Sacco's books. Palestine is a fantastic piece of comics-journalism--and is the first book that could claim that title at all. In it, Sacco tours Palestine, talking to the people he meets about their day-to-day lives and about the conflict with Israel. Though Sacco generally presents these conversations without much comment, his sympathy is clearly with the Palestinians and it's difficult to read this book without sharing that sympathy.

I could probably replace this with any of Joe Sacco's books. Palestine is a fantastic piece of comics-journalism--and is the first book that could claim that title at all. In it, Sacco tours Palestine, talking to the people he meets about their day-to-day lives and about the conflict with Israel. Though Sacco generally presents these conversations without much comment, his sympathy is clearly with the Palestinians and it's difficult to read this book without sharing that sympathy.5. American Splendor: From off the Streets Of Cleveland - Harvey Pekar

American Splendor is a series, not a single comic. There are any number of non-fiction books by Harvey Pekar that are worth your time. In addition to this book, I'd especially recommend Our Cancer Year, which is a single-narrative comic about a year relating the story of the year Pekar discovered he had testicular cancer, or American Splendor: The Life and Times of Harvey Pekar, Pekar's first anthology (which I couldn't find on amazon). Pekar's writing is often typified as "slice of life", and if you don't understand what that means, check out these two pages for a taste of American Splendor.

4. Louis Riel: A Comic-Strip Biography - Chester Brown

Chester Brown has gotten a fair bit of press lately for his memoir Paying for It, in which he recounts his experiences as a John. I haven't read that, so I can't say whether it's worth your time. Louis Riel, however, definitely is. Riel is one of the most colourful characters of Canadian history, and Brown writes an energetic and gripping account of Riel's conflicts with the Canadian government. Both his writing and his art are deceptively simple, which increases a kind of unconscious sense that he is presenting you with the simple facts. One of the simple but great things about this book is the endnotes, in which Brown comments on panels which may give a false impression of the history, and corrects that false impression; things like "McDougall arrived in Pembina by ox-cart, not stage-coach. I'm not sure why I drew stage-coaches -- there is a note in my script specifying ox-cart" (246).

3. Persepolis - Marjane Satrapi

Marjane Satrapi's memoir Persepolis and its sequel Persepolis 2 are gripping accounts of life in Iran before, during, and after Islamic Revolution. One of the things that makes this book so engaging is how unfamiliar the story is to most Westerners. This, in addition to the compelling specificity of Satrapi's life, the details of a person that we seem to really get to know, make for a great read. Unlike Maus, which is written by Art Spiegelman about his father and therefore has the benefit of hindsight, Persepolis ends with very little resolution, which is both a weakness and a strength--the lack of a narrativized ending only makes the narrative seem more real.

2. Understanding Comics - Scott McCloud

I've written about Understanding Comics before. It is one of the most popular non-fiction comics ever written, and certainly the most popular non-narrative comic ever written, and deservedly so. In Understanding Comics, McCloud dissects the medium of comics in both historical and especially in theoretical terms, and attempts to explain how comics work. He does so in an entertaining and engaging way that is well worth reading by anyone who enjoys the medium of comics.

1. Maus - Art Spiegelman

Before he wrote Maus, Art Spiegelman was known by comics fans for his experimental--sometimes radically so--art. In comparison with some of his other work, Maus is deceptively simple and straightforward. It is the story of Spiegelman's father, Vladek, a Polish Jew, during and after WWII. Spiegelman couches the story as an animal fable, drawing the Jews as mice, the Germans as cats, the Americans as dogs, etc. The only comic book ever to have won a Pulitzer Prize, this is both an outstanding comic book and an outstanding holocaust narrative.

And there you have it. This list isn't to say that there aren't plenty of other non-fiction comics which are also worth your time of course. Feel free to suggest more in the comments!

Thursday, January 19, 2012

Man and Superman

Formalism and structuralism both focus on the work of art as an object independent from the people or the world that created them. But plenty of kinds of criticism does care about things outside the work of art as an artifact. The biography of the authors, the historical moment out of which the work arose, the influences upon the work and its influences on other works, all of these focus outside the work itself.

Superman arose out of a specific historical moment.

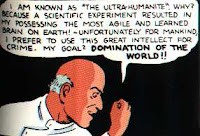

As you may know, Superman was created by artist Joe Shuster and writer Jerry Siegel. In 1938, when the first Superman comic was published in Action Comics #1, Siegel and Shuster were both 24 years old, and they'd been working together on Superman for at least five years. Their first published Superman work was their short story "The Reign of the Superman", published in a 1933 fanzine. That original story featured a bald "Superman" bent on world domination: recognizable now as an early version of the Ultra-Humanite, who was himself an early version of Lex Luthor.

The origin of the name "Superman" is up for debate, but in the 1930s there was another historical movement using the same term. Adolph Hitler (who became chancellor of Germany in 1933) was strongly influenced by his reading of Nietzsche and by the idea of the Ubermensch, which in English translations of the day was given as "Superman". Hitler considered himself to be the Superman, who by strength of will could, and SHOULD, overcome lesser men and exert his power. Hitler, of course, applied Nietzsche's ideas along racial lines, and considered the Arians to be a race of Supermen, who would use their will to dominate lesser races.

Siegel and Shuster, Harry Donenfeld, Jack S. Liebowitz, Sheldon Mayer, (not to mention Bob Kane, Will Eisner, Jack Kirby, Stan Lee) were all Jewish. Though Siegel has said that he never read Nietzsche and he wasn't thinking of Hitler, in 1938 a Jewish-American community created and published a story about a dark-haired alien* Superman who used his power not to dominate but to protect the weak, and who exerted his power on behalf of so-called "lesser men". Superman's first acts in the comics include saving a woman wrongly accused of murder, stopping a man from beating his wife. Whether his creators intended him to be such or not, then, Superman is a direct refutation of the Nazi idea of the Ubermensch.

*We should understand "alien" not only as a science-fiction designation, but as a racial one. Superman is defined as an outsider. He's not an Arian, but he's not Jewish either, exactly. He's a stranger in a strange land--though that is itself a designation that has often historically been adopted by or thrust upon Jewish people.

Superman arose out of a specific historical moment.

As you may know, Superman was created by artist Joe Shuster and writer Jerry Siegel. In 1938, when the first Superman comic was published in Action Comics #1, Siegel and Shuster were both 24 years old, and they'd been working together on Superman for at least five years. Their first published Superman work was their short story "The Reign of the Superman", published in a 1933 fanzine. That original story featured a bald "Superman" bent on world domination: recognizable now as an early version of the Ultra-Humanite, who was himself an early version of Lex Luthor.

The origin of the name "Superman" is up for debate, but in the 1930s there was another historical movement using the same term. Adolph Hitler (who became chancellor of Germany in 1933) was strongly influenced by his reading of Nietzsche and by the idea of the Ubermensch, which in English translations of the day was given as "Superman". Hitler considered himself to be the Superman, who by strength of will could, and SHOULD, overcome lesser men and exert his power. Hitler, of course, applied Nietzsche's ideas along racial lines, and considered the Arians to be a race of Supermen, who would use their will to dominate lesser races.

Siegel and Shuster, Harry Donenfeld, Jack S. Liebowitz, Sheldon Mayer, (not to mention Bob Kane, Will Eisner, Jack Kirby, Stan Lee) were all Jewish. Though Siegel has said that he never read Nietzsche and he wasn't thinking of Hitler, in 1938 a Jewish-American community created and published a story about a dark-haired alien* Superman who used his power not to dominate but to protect the weak, and who exerted his power on behalf of so-called "lesser men". Superman's first acts in the comics include saving a woman wrongly accused of murder, stopping a man from beating his wife. Whether his creators intended him to be such or not, then, Superman is a direct refutation of the Nazi idea of the Ubermensch.

*We should understand "alien" not only as a science-fiction designation, but as a racial one. Superman is defined as an outsider. He's not an Arian, but he's not Jewish either, exactly. He's a stranger in a strange land--though that is itself a designation that has often historically been adopted by or thrust upon Jewish people.

Labels:

comics theory,

history,

major authors,

superman

Wednesday, January 11, 2012

Hello?

Is there anybody out there? Just nod if you can hear me.

I really disappeared, didn't I? But I'm back and I'm going to try again.

Stay tuned.

I really disappeared, didn't I? But I'm back and I'm going to try again.

Stay tuned.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)